Memory traffic is the bottleneck#

The culprit of performance degradation can almost always be attributed to memory traffic. In this tutorial, we’ll discuss a couple things:

How memory is accessed by the CPU.

How we can write code to minimize memory traffic and ultimately make our code as efficient as possible.

A model for the CPU#

To understand how and why a certain optimization works, we need to understand a basic high-level model of the central computing unit, or CPU, of a computer. For our purposes, the CPU consists of

A set of computing units. These perform operations on numbers.

Cache. This is a type of memory with incredibly fast memory bandwidth. This means it transfers data to the computing units quickly.

There’s usually more than one type of cache. The typical hierarchy is L1, L2 and L3. The first has the fastest memory bandwidth and lowest capacity. The last has the slowest memory bandwidth but the largest capacity.

You might have heard of random access memory, or RAM. Cache memory is much much faster than this!

Registers, which are even faster than cache. But for the most part, we’ll only consider the computing units and the cache.

Cache hit and cache miss#

When a code block is executed, your computer will first search for the variables in the cache. If the variable is not found in the cache, the CPU must load the memory of the variable into cache. But loading a single piece of memory is uneconomic, so instead a cache line is loaded. This is a strip of memory addresses. We refer to this process as a cache miss.

If the variable is loaded into memory, we refer to it as a cache hit. Ideally, we want to maximize the likelihood of a cache hit when we write code. This is generally what optimization of memory bottlenecks is about.

Row- and column-major order#

It’s important to understand how your computer allocates memory when you’re writing code. If you make a mistake here, it will severely impede the execution speed of your code! But why?

For the most part, this will be relevant knowledge when we’re working with matrices.

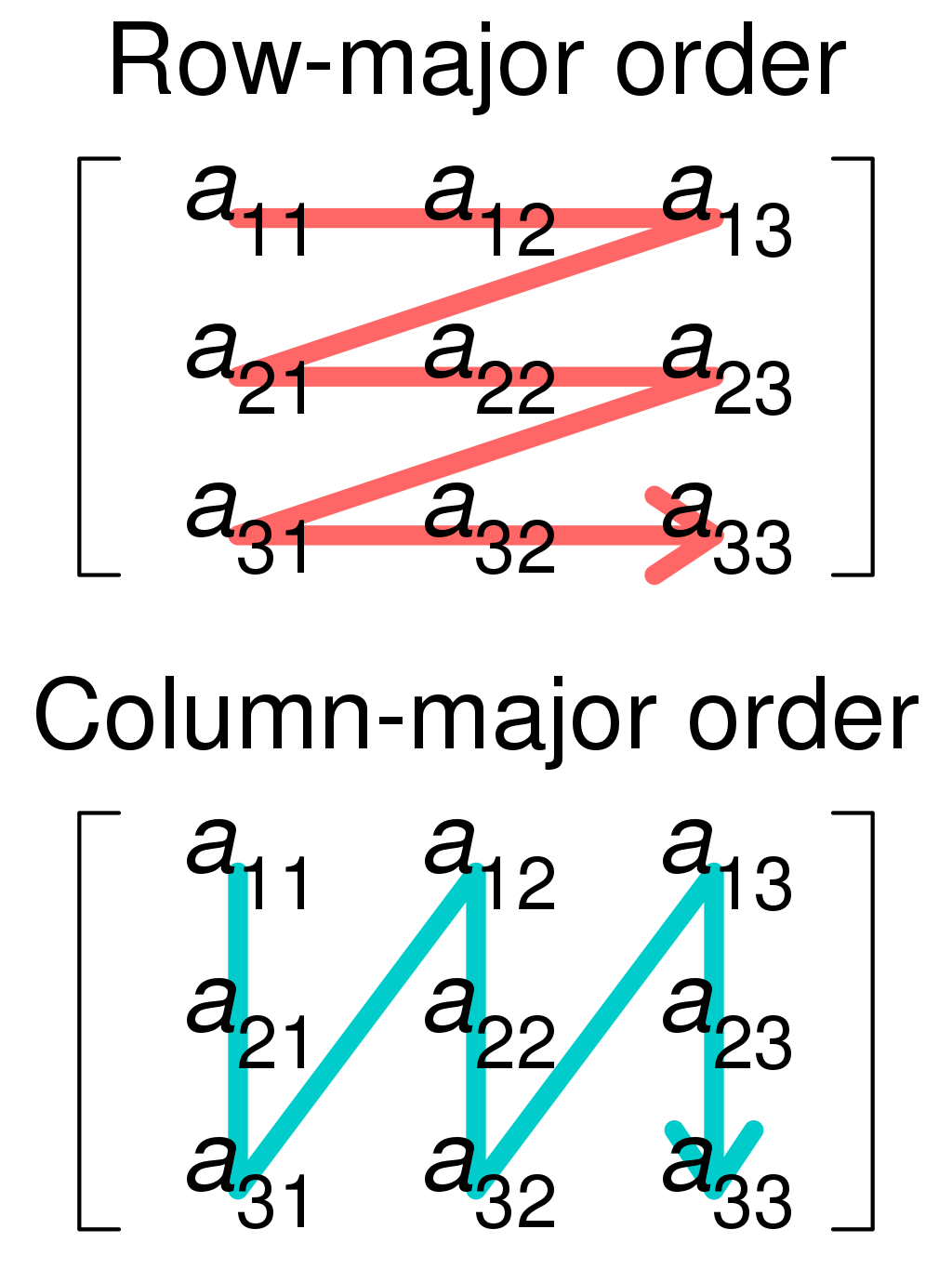

Fig. 2 Illustration by Cmglee, taken from Wikimedia Commons.#

Row-major order#

In C and C++, memory is allocated in what is known as row-major order. For a matrix A[i][j], any two elements on a row i is adjacent to each other in memory. We say that the elements on the row is allocated contiguously.

When the underlying memory is allocated as row-major, we should traverse the rows (i.e. the innermost loop should be over the column index) to reduce the stride through memory. Stride means how many memory addresses we skip over before we reach the desired memory address. If the memory address lies right next to the last one, it’s called stride-1. If it lies N addresses away, it’s called stride-N.

Column-major order#

When memory is allocated in column-major order, each column j in a matrix A[i][j] is allocated contiguously instead. Fortran is a programming language that does this.

We should traverse the columns (i.e. the innermost loop should be over the row index) to reduce the stride in memory when the underlying memory has column-major order.

Note

Armadillo, the linear algebra package for C++, allocates memory in column-major order! If you use this, you must be careful about how you stride through matrices.

Illustrative example#

We’ll do an example with Armadillo, because it simplifies allocation of matrices significantly. We recall that Armadillo allocates memory in column-major order. Therefore, we should make sure to traverse the matrix along its columns (stride-1)! This means that we let the innermost loop be a loop over the row index (here i):

int n = 10000;

mat A = mat(n,n);

clock_t start = clock();

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++){

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++){

A(i, j) = i + j;

}

}

clock_t end = clock();

double timeused = 1.*(end-start)/CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

cout << "timeused = " << timeused << " seconds " << endl;

which outputs

timeused = 0.474549 seconds

If we instead stride along its rows (stride-n)

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++){

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++){

A(i, j) = i + j;

}

}

we get

timeused = 0.96181 seconds

which is roughly twice as long. Conceptually, cache misses occur much more frequently in a stride-n code. Cache lines that are already loaded must be discarded in favor of loading new cache lines. Part of the execution time leaves the computing units idle, waiting for the correct memory addresses to be loaded into cache before they can do any computation.

Temporaries#

We can often help the compiler by creating temporary variables, or temporaries, to reduce memory traffic. This is easiest to showcase with a few examples:

Example 1: matrix-vector multiplication#

Let’s look at a simple example of matrix-vector multiplication.

mat A = mat(n,n).randu(); //Randomlly generated matrix

vec x = vec(n).randu(); //randomly generated vector

vec y = vec(n).fill(0.);

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++){

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++){

y(i) += A(i, j)*x(j);

}

}

Execution speed for n = 25000:

timeused = 8.70447 seconds

On the surface, this looks like a perfectly sensible solution. But there’s a few problems:

x(j)is certainly not dependent on the inner loop. By including it there, it’s repeatedly discarded and loaded into cache.A(i, j)only partially depend on the inner loop. So here we face the same problem. Cache lines that are loaded in must be discarded to make room for new ones.

Let’s deal with point 1 first. Instead of loading the vector, we create a temporary tmp for it:

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++){

double tmp = x(j); //Extract element j of the vector

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++){

y(i) += A(i, j)*tmp;

}

}

Execution speed for n = 25000:

timeused = 6.76226 seconds

So we’re seeing improvements. Now, let’s fix point 2. We can load a column of A(i,j) using A.col(j):

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++){

double tmp = x(j); //Extract element j of the vector

vec tmp_vec = A.col(j); //Extract column j

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++){

y(i) += tmp_vec(i)*tmp;

}

}

Execution speed for n = 25000:

timeused = 6.23306 seconds

so we’re still seeing improvements. Don’t be fooled by the small absolute difference; this is 40% faster than the original code!